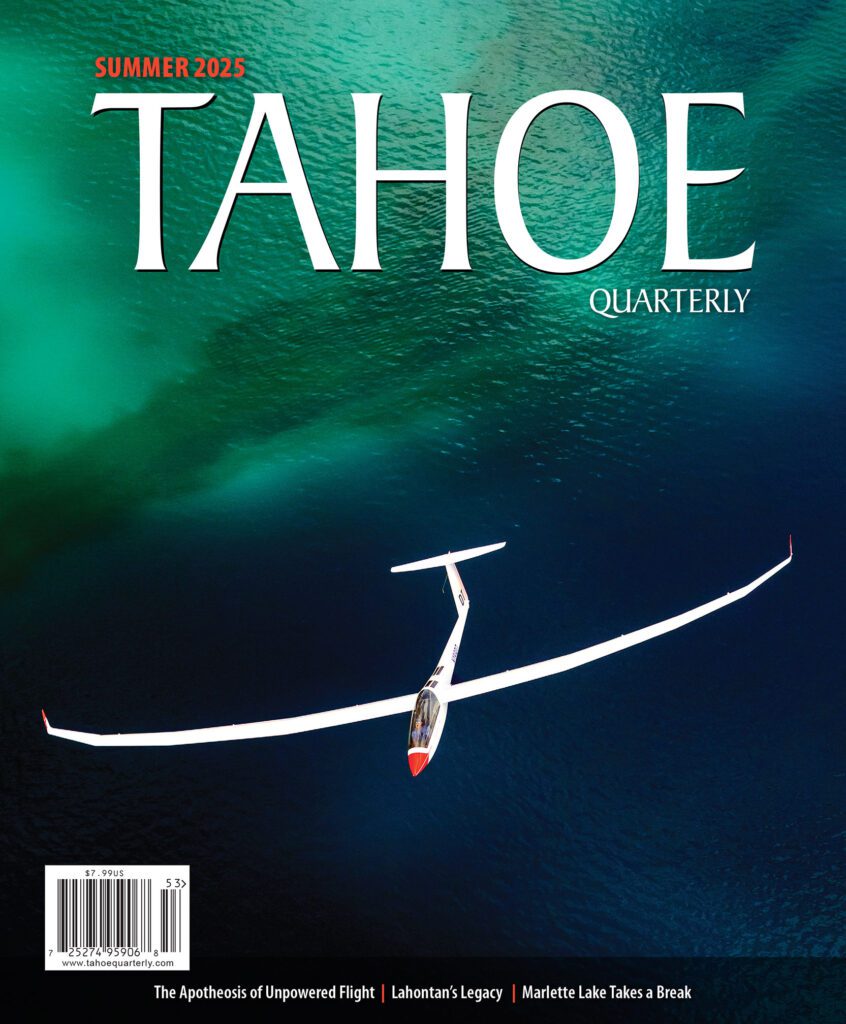

The single-engine airplane’s stall warning kept beeping while I stuck my head out the window a few thousand feet over Lake Tahoe. I could barely hear it over the sound of 100 MPH wind echoing in my headset as it struck the microphone near my lips. I ignored all of it. My job was to catch the perfect shot of Gordon Boetteger’s glider sailing through the air for Tahoe Quarterly magazine’s summer 2025 cover story.

My pilot, Silvio Ricardi, pumped the throttle and worked the yoke to keep the Carbon Cub aloft, while also ensuring the side window stayed open so I could stick my head and camera outside the cockpit without getting smacked in the face. Too fast, and the window slams shut; too slow, and we stall.

The Carbon Cub is uniquely built for this task, both with “an extremely slow stall speed,” according to its sales brochure, a fully openable side window, and ability to land anywhere should we need to. Silvio also has extensive experience flying in the Australian bush with this airplane, he said.

Four days before, the editor of TQ asked if I was available for this feature story on late notice. I responded “YES!” immediately, then called Gordon to coordinate airport time and get advice on focal length. I arrived at the Minden-Tahoe Airport on a Friday morning and met the crew. They told me I could give the pilots instructions from the passenger seat, and not to be shy about it, either.

They both knew this would be my first air-to-air photography assignment, but I wanted to impress them, so I played it cool.

After getting some environmental portraits on the runway, another pilot towed the glider out over Lake Tahoe while Silvio and I followed. Even though Gordon’s Schempp-Hirth Arcus J glider has a self-starting turbojet engine, the tow helped him save fuel. Once the glider detached from the tow plane, it was just the three of us in the air.

Learning as we flew

We started with comparatively easy shots over Sand Harbor and with Gordon flying alongside us so that I could get a clear view of his face with a Top Gun-esque thumbs up.

It took me a while to understand the perspective shift that occurs when Gordon sees himself over an object, such as the beach, and we see him from several hundred feet away and above, with mountains as a backdrop. Framing and composition on the ground feels a little more straightforward.

We captured some shots of him with the clouds behind him while making a second run for Sand Harbor to try again. As the glider came back down, it started to become evident how different an engine-driven airplane with 35-foot wingspan operates from a glider with 65-foot wingspan.

Managing our relative positions was challenging for the pilots, and finding the exact spots to shoot from to avoid catching our own airplane’s wings in the shot was equally difficult for me. Traditional air-to-air photographers sit in a cargo plane facing backward, capturing a clear view of the airplane following the photographer.

Well, if you happen to know anyone with a cargo plane sitting around, please let me know.

As Gordon came down out of the clouds, I buried my face in the viewfinder and told Silvio to bank right, tilting the aircraft. I dipped my face and camera over the edge of the cockpit down toward the blue waters below. I held the shutter button down, capturing 10 frames per second, while fighting the wind as it tried to tear the camera out of my hands. I stabilized my body against the canvas chair and followed the glider under us, all while trying not to kick the second set of rudder pedals or passenger yoke.

The glider was so close that even the minimum focal length of 100mm couldn’t capture the full airplane in the frame.

Before I could check my screen, we were heading out over Emerald Bay. By then, we had all been flying for a while. I had already shot a few hundred frames as I grew accustomed to positioning my body in the soft seat, sticking my camera out the window, and learning what to tell the pilots.

Getting THE shot, over and over

We wanted an Emerald Bay backdrop because it seemed so iconic. As Gordon flew up over the Sierra range to pick up speed, we lost him briefly on the horizon. A few moments of terror overcame me, as we both spun around looking. When we found him, he was ahead of us. We had to catch up as the glider picked up speed across the mountain air.

We tried to stay ahead and to the east to place Emerald Bay behind Gordon. But he viewed himself as flying over the bay already, while we saw him as flying out over the trees. Gordon started turning back toward the Lake when I told him to fly back toward Fannette Island.

Gordon pulled the glider into large horizontal arcs back toward Vikingsholm Castle, then back toward us. Lining up the first Emerald Bay shot was literally one in a hundred, with only a few seconds for all the elements to align. I got two shots with the island and airplane lined up. Within moments, we were over South Tahoe Keys already.

Finally, I was able to check my screen to see what we had. Frantically searching through hundreds of photos, I found one that I liked, but I wasn’t sure that I loved (above). Silvio and Gordon kept asking if I got the shot, and I felt like I wanted one more try…just to be safe.

So we turned around and tried again. We decided to catch some beach shots because Emerald Bay was not very emerald that day. We saw a patch of green further north and lined it up for some more pictures.

As the glider headed out toward open water, Silvio and I took another turn down toward the water and a hard right with the tail rudder spun us around. Gordon pulled up, pointing the glider toward us. I struggled to keep up and maintain hold of the lens while managing the polarizer and zoom ring. At first, I thought the image was just OK, because I didn’t know if the polarizer had cut the reflections or if we lined up the colors, so I dismissed the image as we headed toward Emerald Bay again.

This time, lining up the shot got harder because the glider was moving faster. In our final attempt, we were tragically misaligned, so I instructed Silvio to tilt and spin again, allowing me to frame the airplane between the bay’s entrance banks as we shot ahead of Gordon, all the while battling the window. Finally, I saw the moment and told Silvio to “slow down!” The stall warning beeped loudly again, the G-forces pressed us down into our seats, and we spiraled down and toward the glider.

I could hear Silvio fighting against the forces, jerking the throttle up and down to maintain minimum air speed. He asked what I needed. But I was zeroed in, I told him it was all good.

Panic set in as I tried to track the glider, stabilize the camera, and keep everything in the frame. I mashed the shutter button, seeing the glider intermittently between black frames as the mechanical shutter covered the viewfinder 10 times per second. I finally synced up my movement with the glider, and felt that joy in my chest when I felt like I had locked in.

The moment passed. As we pulled out of the stall and started flying east again, Silvio and Gordon asked if I got the shot. I started spinning through all the images and finally saw one single frame that didn’t clip the wings off the glider.

I said yes, we got it. And relaxed.

As we leveled out, I grabbed the bottled water over my head and chugged. I had been ignoring the nausea. Silvio could probably hear my breathing through the headset and asked if I felt sick.

“Yes, a little,” I said.

“Me, too,” he said.

For the rest of the flight, we sat quietly facing forward, drinking our waters, with no turns, no bumps, and no stalling. Just a nice smooth ride back to the runway.

Choosing the final shots

For the rest of the day, I poured over 1,100 shots to pick out the 24 I’d send to the magazine. Something about the close-cropped overhead shot felt intimate, so I picked that one. It became the opening spread. The image with the green to blue water, once cropped and toned, looked stunning. It became the cover. The first Emerald Bay picture stunned and delighted with its alignment and ended up on an inside page. But the second one, the one that made us sick, did not make it in, probably because it was missing the well-known island.

In the end, the Tahoe Quarterly team picked seven shots for a fantastic story and well-designed cover and spread. And I can’t get over how amazing that feels. So let me know if you own an airplane and need some pictures of it in the air. 😉